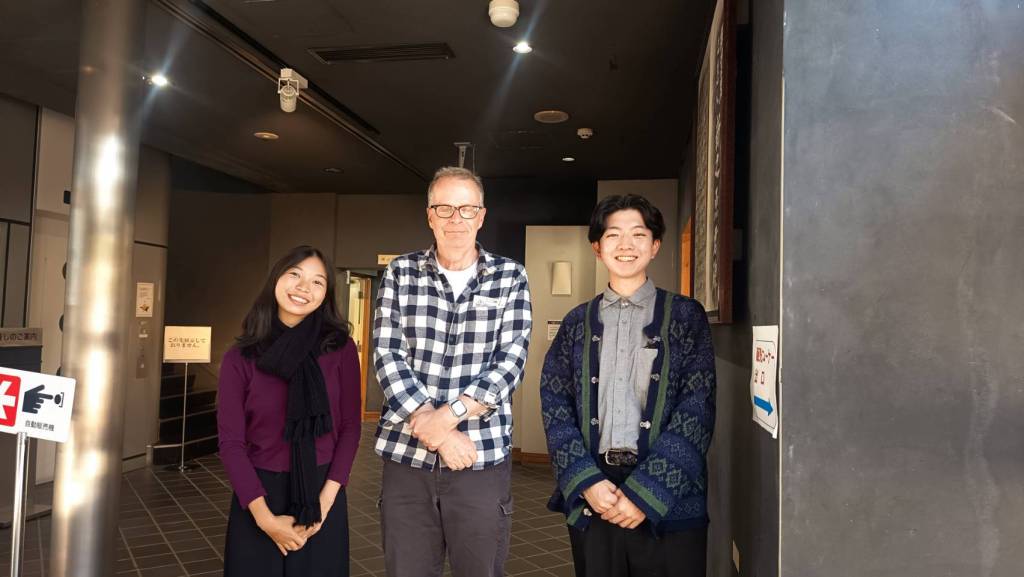

By Shintaro Yagi, Susanti and Yakumo Yokoyama

A white man wearing glasses curiously touched the water filled with paper fibers in a large tub. The water was cold, and the fibers stuck to his fingers. The air in the room smelled a little like wet wood and fibers, a mixture of river water and the old wood that had absorbed water and seeped into the workshop walls.

Johan, a visitor from Sweden, is spending only a few days in Kochi Prefecture. On his third day, he finds himself inside the Tosa Washi Paper Museum in Ino Town, sleeves rolled up, listening closely as a staff member explains how to tilt the frame.

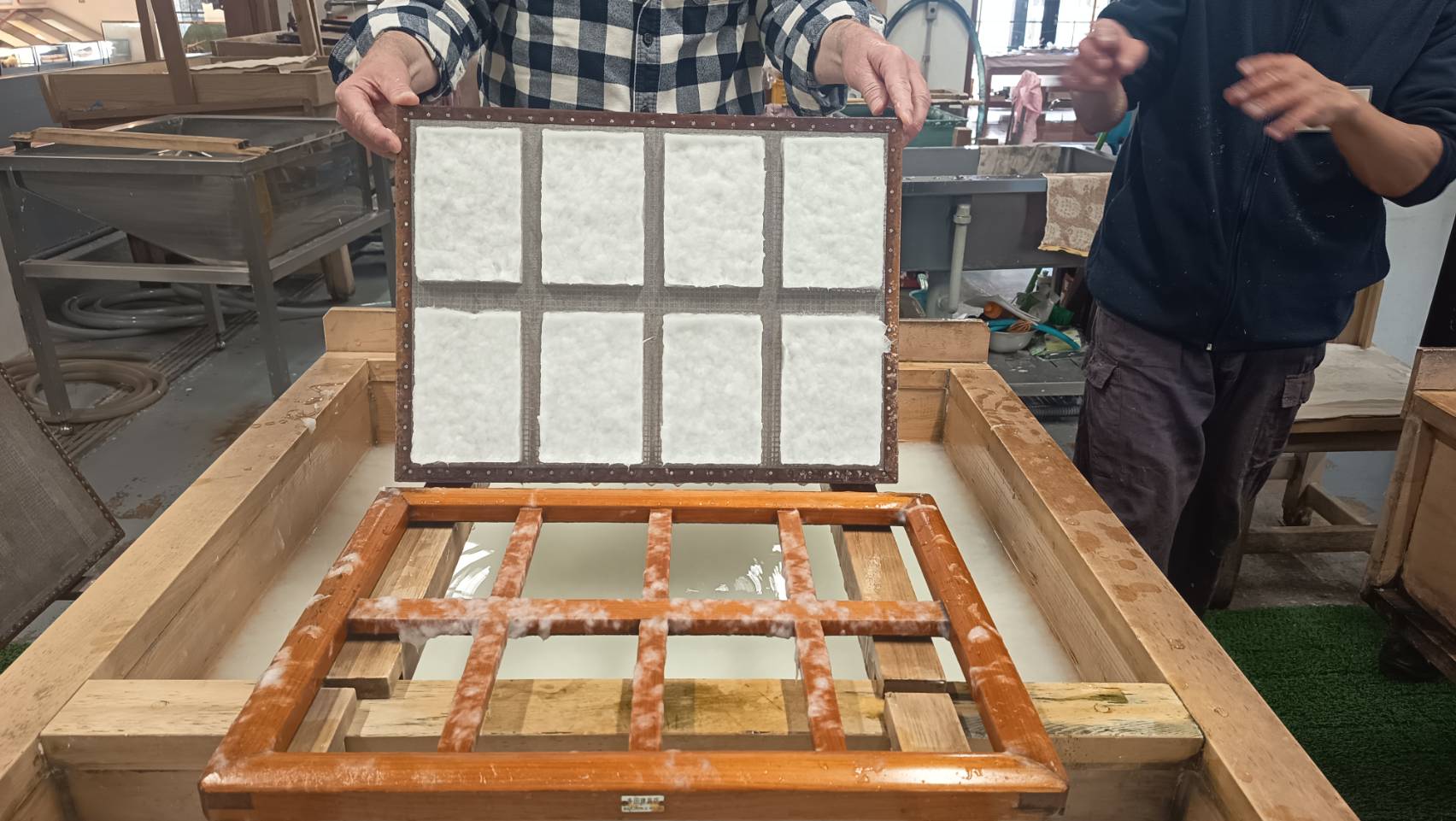

“If you shake it too much, it becomes uneven,” Mori-san, the guide, says to him in careful English. He shows the movement slowly with his hands. Around them, several visitors stand close, observing how to move the Tosa Washi frame. The process seems simple, but after trying it, it feels kind of slow and tiring because it requires physical control.

“I like making Tosa Washi. Yeah, It’s so fun to make,” said Johan after finishing his sheet. He stared at the paper in the frame as water continued to drip onto the floor. He smiled and moved his fingers slightly. “I wonder what the paper will be like.”

Johan is one of many visitors from overseas who come to the museum to experience traditional papermaking, even though the use of washi is continuously declining in Japan.

Handmade washi has been replaced by machine-made paper and digital technology. As a result, washi is no longer used in everyday life, and the communities that have supported Tosa Washi for generations are now facing problem that is getting worse.

Actually, this story is not just about paper. It’s about how the local crafts like Tosa Washi can survive the social and economic changes in rural Japan. When crafts strongly connected to place, labor, and community begin to disappear, something more than just a product is lost.

Tosa Washi is different from other ordinary paper. It is the result of a blend of nature, tradition, and human skills that have worked together in Kochi for many thousand years. Craftsmen here often defining Tosa Washi through three inseparable elements: material, place, and method.

First, the material. Tosa Washi is made from plant fibers, such as kozo, mitsumata, and gampi, unlike regular paper that is made from wood pulp. These plants grow in the mountainous area of Kochi. Their fibers are long and strong. This makes the paper thin, butit’s still durable. The use of these plants is no coincidence but rather the result of generations adapting the papermaking process to the local environment.

Second is the place. Papermaking in Kochi developed alongside its rivers, including the Niyodo and Shimanto rivers, which are often described as among the clearest in Japan.

Clean water is important in making Tosa Washi papermaking because it affects the final paper’s color, texture, and how strongly it can be used. Even a little bit of dirt can leave stains on the paper.

Because of this, papermaking communities formed near rivers where clean water was always available. For more than a thousand years, Kochi’s natural environment has quietly supported the continuation of this craft.

“Be relaxed, or you can’t keep the frame horizontal,” Mori-san says as he watches Johan’s Hands.

“Scoop the material quickly and lift it,” he adds.

Finally, there’s the method. Tosa Washi’s method is where it becomes clearly human. It uses a technique called kamisuki. Kamisuki is a technique where the papermaker uses a wooden frame to gently shake the paper pulp to spread the fibers. To do kamisuki, experience is important part because even small differences in rhythm or pressure can change how thick and textured the paper is. No two sheets of washi are exactly same. Each washi reflects the person who made it.

The handmade quality is Tosa Washi’s strength, but also it becomes the weakness. It gives the paper the cultural and artistic value, but also makes large-scale production almost impossible. In a society that values speed and efficiency, continuing a craft that depends a lot on human resources is a serious problem.

“Tosa Washi has a history of more than a thousand years,” Yamauchi-san, the manager of Ino-cho Paper Museum says.

In the museum, that past is not left abstract and just a mouth story. A detailed model shows daily life in a Tosa Washi papermaking village. There are small figures standing by the river, washing fibers, carrying wood, and working near drying racks. There are two boats in the water, and there are wooden houses built close to the river. The scene shows that papermaking was not just one person’s job, but something the whole community did together. The replica of the papermaking village lets us experience what it was like.There are written records that place Tosa Washi firmly in Japan’s early history. In 927 AD, an important government document from the Heian period called the Engishiki recorded Tosa as a major paper-producing region. According to the record, Tosa paid taxes to the imperial court in Kyoto not with money, but with handmade paper.

For hundreds of years, washi was an important part of daily life in Japan. It was used for important papers, religious books, and everyday things. In places like Ino, making paper was a central part of everyday life, not just a side activity. Families worked together in small workshops. They learned techniques by practicing them over and over. They didn’t need written instructions. Local stories often mention the poet Ki no Tsurayuki. He promoted papermaking in the region.

He also helped create Tosa Nanairo-gami, or Seven-Colored Paper, during the Sengoku period. This paper looks like it was dyed. It was given to the shogun to show the people’s work and the waters of the Ino River.

However, tradition alone was not enough to survive. The “Paper Kingdom of Tosa” continued to exist because it was able to change with the times. At the end of the Edo period, a papermaker named Genta Yoshii improved the tools for making Tosa Washi, such as the sugeta, the same type of Tosa Washi frame used by Johan. By changing the size and balance, he made Tosa Washi production stronger and more efficient. These changes helped support the craft during a time of social and economic change.

Today, Tosa Washi has new purposes in the modern era. “We use Tosa Washi for illustration, historical document restoration, and painting,” said Tanabe-san, a museum staff member.

The paper is also used in calligraphy, interior design, and even products like watch dials. These uses show that Tosa Washi is important to Japanese culture and is still valuable in modern life.

Nevertheless, the future of Tosa Washi remains unpredictable. Within the museum, staff explains this problem not as something abstract, but as a problem they face every day.

“The biggest problem is that demand for paper itself is decreasing,” said Tanabe-san. As the use of washi in everyday life declined, fewer and fewer people chose to make it. “When Tosa Washi stops being made, the papermakers disappear,” he adds. “And when the papermakers disappear, the craftsmen who make the tools disappear as well.”

The loss does not come suddenly. It moves slowly, like water slowly draining away. “As the number of people involved in Tosa Washi decreases, it becomes harder to pass the techniques on to the future,” he explains. “That chain is very hard to rebuild.”The impact of this decline can be seen in papermaking workshops. Many of the papermaker are elderly, and their hands show the marks of years of repetitive work. It takes a long time to learn how to make Tosa Washi. Also, it requires physical strength, patience, and a good sense of rhythm, but it doesn’t guarantee a stable income and good career levels. So, many young people choose safer and more stable jobs outside of this craft.

To solve this situation, Kochi Prefecture and Ino City have started apprenticeship support programs. These programs give young people a opportunity to learn from experts in Tosa Washi. “For example, apprentices learn from papermakers in Uesugi,” Tanabe-san explains.

“The city and prefecture support this kind of hands-on training.” Skills aren’t learned from books, but through daily practice, standing beside a Tosa Washi expert, observing hand movements, and learning when to move and when to wait.

At the same time, the museum has become a place where traditional crafts meet people who may not have been familiar with them before. Japan received more and more visitors from other countries after it reopened after the pandemic. “After the pandemic, cruise ships started arriving at Kochi Port,” Tanabe-san says. “People come by bus tours and in many other ways. More and more people from other countries are visiting every year.”

Today, Tosa Washi is mostly used as an art material, not for everyday use. “It’s mostly used for arts and crafts,” said Tanabe-san. The art of paper tearing, printing, calligraphy, and painting has become a new way for this washi to survive. Washi is colored, torn, layered, and reshaped, which makes it adaptable even when demand for it isn’t high.

Tosa Washi has also received attention for its sustainability. People are discussing how it can help the environment and how it connect to SDGs. But for the people who make it, this idea isn’t new.

“We have more than a thousand years of history,” Tanabe-san says. “We use natural materials from the surrounding environment and make paper in harmony with nature.” From that point of view, Tosa Washi naturally aligns with the ideas behind the SDGs.

“The concept of SDGs came later,” he explains. “But Tosa Washi is already following those ideas.”

By allowing people to experience papermaking directly, the museum encourages a deeper understanding of how traditional crafts can still contribute to a sustainable society, especially in this modern era.

After waiting for his paper to dry, Johan carefully picks up the finished sheet and places it into his bag. “I think I’ll use it to send New Year’s cards to my friends and family,” he says. “I sort of made this paper.”

Soon after, Johan leaves the museum and continues his trip through Kochi. Inside the workshop, new visitors arrive.

What a story! I love the part when they say Tosa washi came first, before SDGs, it actually make sense. Great job of article!

LikeLike

This was such a meaningful article. Tosa Washi is truly a wonderful part of Kochi’s culture!

LikeLike

It such a wonderful article! it inspired me when the article mentioned an important key about how tosa washi can still survive in the modern world.

LikeLike

Tosa Washi is really a genius way to elevate the creativity of a person. We could create something new, figure, quotes, and so much more. By the way, I really loves how the story is told in this article. People need to come and visit Kochi ASAP!

LikeLike

I once had the experience of making Tosa washi when I was child. Since I didn’t know much about its history, I found this article very fascinating!!

LikeLike

I didn’t know beautiful water is important for Tosa Washi. I remembered that I tried to make it when I was an elementary school student. It was a really nice experience for me!!

LikeLike

What a wonderful article. I learned that things once commonplace have now transformed into a culture that deserves protection. I want to help preserve this beautiful culture.

LikeLike

Nice article!

I’ve experienced making a Tosa Washi! It was mysterious and I liked the texture. I think that we need to understand washi has great appeal even though the opportunity to use of washi is declining in daily life.

LikeLike

I felt it was important to preserve traditional Tosa washi for the future. I learn many things about Tosa washi from this article. Thank you.

LikeLike

It so attractive article, I love to make Tosa Washi someday. It’s a traditional papermaking, and Washi was an essential part of daily life for hundreds of years in Japan. It was useful in terms of making books, papers etc. It’s outstanding!

LikeLike